Choice Current Reviews for Academic Libraries Peer Review

Abstract

The Olympic Games claim to be exemplars of sustainability, aiming to inspire sustainable futures around the world. However no systematic evaluation of their sustainability exists. We develop and apply a model with nine indicators to evaluate the sustainability of the 16 editions of the Summer and Winter Olympic Games between 1992 and 2020, representing a total toll of more than than US$70 billion. Our model shows that the overall sustainability of the Olympic Games is medium and that it has declined over time. Salt Lake City 2002 was the virtually sustainable Olympic Games in this period, whereas Sochi 2014 and Rio de Janeiro 2016 were the to the lowest degree sustainable. No Olympics, however, score in the superlative category of our model. Three actions should make Olympic hosting more sustainable: starting time, greatly reducing the size of the event; second, rotating the Olympics among the aforementioned cities; 3rd, enforcing contained sustainability standards.

Main

The Olympic Games are the most watched and the virtually expensive events on Globe. Half the world's population is expected to see coverage of the Tokyo Olympics, when and if they take place in summer 20211. This Summertime Olympics will have triggered expenditures of between U.s.$12 billion and United states of america$28 billion (ref. 2), depending on how i counts. These amounts are not atypical for a Summer Olympic Games3. They brand the outcome i of the most expensive series human interventions in the globe4. Their loftier political priority, and the global attending they attract, requite the Olympic Games the potential to alter controlling at the national and even international levels and to reach people effectually the world.

The large expenditure and exceptional political leverage of the Olympic Games nowadays a chance to pioneer necessary sustainability transformations5 well across the trillion-dollar event industryhalf-dozen. Predominantly an urban mega-project7,8, the Olympic Games could show especially useful in addressing the looming sustainability challenges for cities in an age of rapid urbanization: reducing greenhouse gas emissions, guaranteeing social peace and justice, providing sustainable mobility and curbing urban sprawlix,10. Together with their exceptional visibility, the Olympic Games provide a unique platform to achieve a global audience and could serve every bit a model for cities, countries and other events around the world to emulate.

Academic stance, however, is divided regarding the sustainability of mega-events such as the Olympic Games. While some scholars doubt whether mega-events tin ever exist sustainable, others extol their virtues. The onetime group criticizes mega-events as paying mere lip service to sustainability while pursuing a business model that plays to elite interests, global consumption and transnational investment flows11,12,xiii,14,15. The latter group, by contrast, considers mega-events as windows of opportunity to push button and showcase innovative solutions to global challenges and every bit political levers for moving towards sustainable practices of living and consumption16,17,xviii,19.

That the Olympics be sustainable is a requirement laid down in the contract between Olympic host cities and the International Olympic Committee (IOC). Sustainability is 1 of the three pillars of the IOC'southward road map for the future, Olympic Agenda 2020, and features prominently in its continuation, Olympic Agenda 2020 + 5twenty. The IOC's sustainability strategy aims to "ensure the Olympic Games are at the forefront in the field of sustainability"21. In 2018, the United nations passed a resolution that alleged "sport as an enabler of sustainable development"22 and signed a letter of intent highlighting the contribution of the Olympic Games to the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs)23. Nonetheless, in that location is a notable absence of systematic studies that interrogate such claims. The IOC fabricated an effort in the early on 2000s to prepare a coherent measurement of the impacts of the Olympic Games in each host city over a period of more than ten years, in an attempt to foreground sustainability objectives24. Only the Winter Olympics in Vancouver in 2010, however, completed the full cycle of this so-called Olympic Games Impact study, and it was subsequently abandoned in 2017. The few independent attempts to evaluate the sustainability of the Olympic Games, and of mega-events more by and large, are limited to one edition of the event and operate with incommensurable models that make longitudinal comparisons impossible.

Against this background, this contribution evaluates the sustainability of the Olympic Games in a systematic longitudinal study. It analyses the 16 editions of the Summer and Winter Olympic Games from Albertville 1992 to Tokyo 2020 (N = sixteen) (ref. 25). This sample represents full sports-related costs of more than US$70 billion, not counting the cost of ancillary infrastructure, which is often multiple times higher3. It represents an important advance both for sustainability scholarship and for sustainability policy. For scholars, it offers a model for conceptualizing and empirically evaluating the often diverging claims regarding the sustainability of humankind's largest and most expensive result. For decision makers, it provides empirical data for policy outcomes26, answering the question to what degree hosting the Olympics can or cannot contribute to sustainability goals.

Results

Sustainability remains an elusive concept in the Olympic Games, and in mega-events more generally. Every Olympic Games now claims to be sustainable, but all equally neglect to provide a coherent definition or model for independent evaluation24,27,28.

Definition and model

Filling this lacuna, nosotros start develop a definition and conceptual model of the sustainability of the Olympic Games, depicted in Fig. 1. We define 'sustainable Olympic Games' forth three dimensions: having a express ecological and material footprint, enhancing social justice and demonstrating economic efficiency. This definition reflects current debates on sustainability as minimizing resource utilize while guaranteeing minimum thresholds of social and economic well-being29. The model strikes a residual between potent conceptions of sustainability, which would put ecological limits over social and economic gains, and weak conceptions of sustainability, which would see the ecological, social and economic dimensions as mutually substitutable and accept a stronger focus on social and economic developmentthirty. It ties into policy debates on sustainability such as the 17 United nations SDGs, which envision just human being development while decoupling resource consumption31, and the Paris Agreement32.

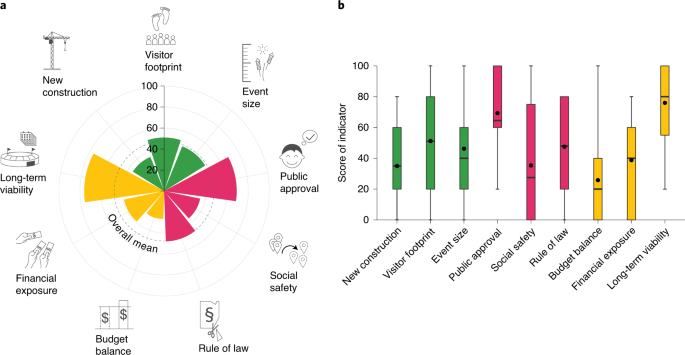

The definition and model assign equal weight to the classic three dimensions of sustainability (inner ring—ecological, social and economical), evaluating them with 3 indicators each (outer ring).

The conceptual model further subdivides each of the three dimensions of sustainability into three indicators (indicated with icons in Fig. ane) that nosotros measured for each Olympic Games from 1992 to 2020.

From this conceptual model, we develop a score carte for measuring sustainability24. We score each of the 9 indicators on a scale from 0 to 100, where 0 means 'least sustainable' and 100 'most sustainable'. In assigning equal weight to each dimension, we right for the predominant focus of existing studies on the economic impacts of events and on 'greening' (waste reduction, ecology impacts, eco-certification and and so on), at the expense of the social dimension27,33,34,35.

We then apply the model to all Olympic Games since 1992 (N = 16), on the basis of our database25. The year 1992 marks the beginning of a period of potent growth in the size of the Olympic Games36, bringing challenges of sustainability to the fore. At the same time, ideas of sustainability started to gain more traction with the Earth Peak in Rio de Janeiro, and sustained attention to ecology issues in the Olympic Games started to emerge. Supplementary Table ane provides full details of each indicator, and the Methods section explains the approach to constructing the model and the score card.

Overall sustainability

Overall results in Fig. 2a demonstrate that the sustainability of the Olympic Games from 1992 to 2020 is medium, at 48 out of 100 points possible. Mean scores for each of the three dimensions fall within a narrow range of 44 (ecological dimension) to 47 (economic dimension) and 51 (social dimension). Sustainability is therefore fairly consistent across the three dimensions.

a, Mean values of nine sustainability indicators. b, Distribution of values. Dots show the mean value; middle lines testify the median; box limits show upper and lower quartiles; whiskers testify maximum/minimum. Encounter Supplementary Information for full descriptive statistics.

There are, all the same, important differences between the scores of indicators. 'Budget residual' shows the lowest value (Chiliad = 26), underscoring the Olympics' consistent history of price overrun3. 'New construction' and 'social safety' as well receive poor ratings (1000 = 35 for both), indicating that extensive construction of new sports venues and the displacement of people are regular occurrences in the training for an Olympic Games. By dissimilarity, the Olympic Games have a relatively stiff tape in finding adequate afterwards-use for the key sports and not-sports venues, as expressed in the indicator 'long-term viability' (Yard = 76). This finding suggests the need to revise the dominant opinion that the event leaves numerous so-chosen white elephants, that is, oversized and underused sports venues37,38,39. On average, the Olympics in our sample besides relish loftier public blessing (1000 = 69).

The mean values disguise considerable variance in the scores of each indicator across the 16 Olympic Games in the sample (Fig. 2b). Scores range on the full calibration from 0 to 100 for 6 out of the nine indicators. This ways that there is little consistency in how individual Olympic Games score on the indicators, with both very high and very low scores present. The presence of very loftier values (between lxxx and 100) on each of the indicators also suggests that, in general, information technology has been possible to obtain high scores, and it is therefore conceivable to have much higher overall sustainability scores than the middling ones in our sample.

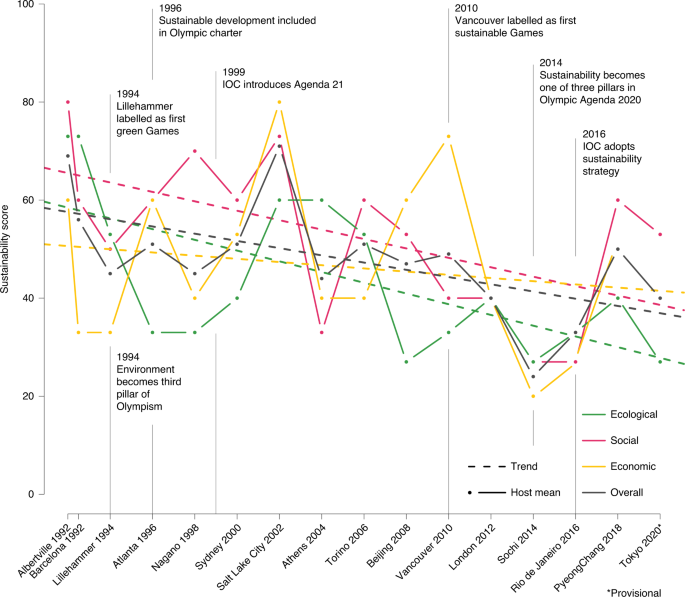

Development over time

During the period covered in our sample, the IOC and Olympic organizers adopted global policies such as Calendar 21 and the SDGs and applied them to the Olympic Games40. Our data evidence, nonetheless, that despite these measures, the sustainability of the Olympic Games has decreased over fourth dimension (r overall = −0.59, P < 0.05). This negative trend becomes evident from Fig. 3. It holds true for all simply the economic dimension, with the ecological tape declining the most (r ecological = −0.65, P < 0.01; r social = −0.56, P < 0.05). The Wintertime Games in Vancouver in 2010 were the first to be proclaimed as sustainable Games41. Yet, the Olympics held before Vancouver 2010 were more sustainable than those from Vancouver onward: Olympic Games from 1992 to 2008 have a mean sustainability score of 53 points, whereas those since Vancouver 2010 stand at only 39 points—a statistically significant divergence (t(14) = −2.fourscore, P = 0.01). The promotion of the environment and sustainability to a pillar of the Olympic policy agenda, as illustrated in Fig. 3, has not been able to stop or reverse the decline of sustainability over time.

Sustainability is decreasing overall and in its ecological and social dimensions. Dots bespeak individual values of the Olympic Games; dashed lines betoken linear trends. All trend lines, except for the economic one, are significant at P < 0.05.

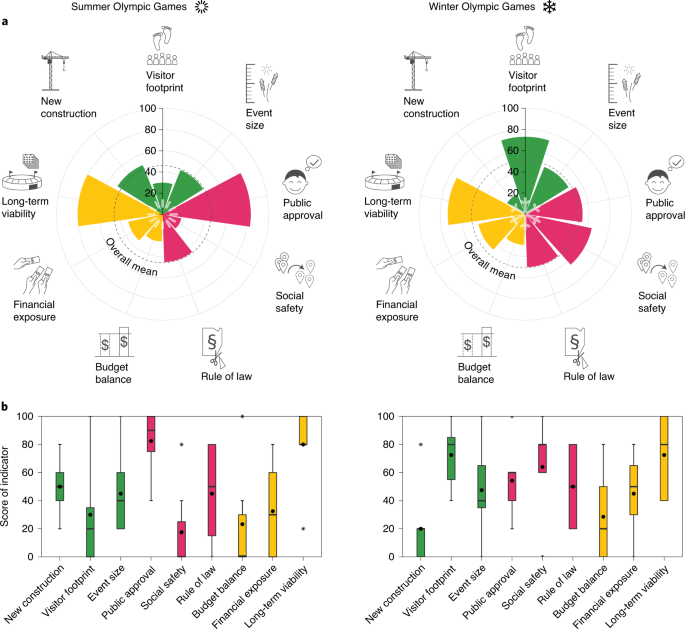

Differences between Winter and Summer Games

The Summer and Winter Olympic Games have like overall sustainability (M Summer = 45, M Winter = 51, t(14) = 0.98, P = 0.35). There are, however, strong divergences between the scores of individual indicators, as displayed in Fig. 4. The Winter Games have a significantly smaller visitor footprint (t(14) = −two.65, P = 0.02) than the Summer Games. The Winter Games have too grown much less than the Summer Games and displace fewer people, which is probably due to the smaller size of the required venues and urban infrastructure (t(xi) = −ii.32, P = 0.05, marginally in a higher place the threshold for statistical significance). By contrast, the Summer Games have a significantly lower share of new venues (t(14) = 2.65, P = 0.02). The specialized venues required for the Winter Games, such as ski jumps and bobsleigh tracks, might contribute to that result. The Summertime Games also garner college blessing than the Winter Games (t = 2.15, P = 0.05, marginally above the threshold for statistical significance), mayhap considering winter sports appeal to a smaller share of the population. All other differences are not statistically significant.

a, Hateful values of nine sustainability indicators. Summer and Winter Olympic Games take similar overall means but substantial divergences for individual indicators. b, Distribution of values. Dots show the mean value; middle lines show the median; box limits show upper and lower quartiles; whiskers show maximum/minimum; asterisks show outliers (one.5 times the interquartile range in a higher place the 75th percentile or below the 25th percentile). Run into Supplementary Information for total descriptive statistics.

The sustainability record of the Winter Games fluctuates much more than than that of the Summer Olympics (SDSummer = eight versus SDWinter = 15). The extremes of the overall scores of the Winter Games range from a high of 71 points (Salt Lake City 2002) to a depression of 24 points (Sochi 2014), compared with the more than moderate extremes of 56 points (Barcelona 1992) and 29 points (Rio de Janeiro 2016) for the Summertime Games. These findings suggest that hosting the Winter Games is more probable to result in either significantly more or significantly less sustainable Olympic Games, compared with the hateful.

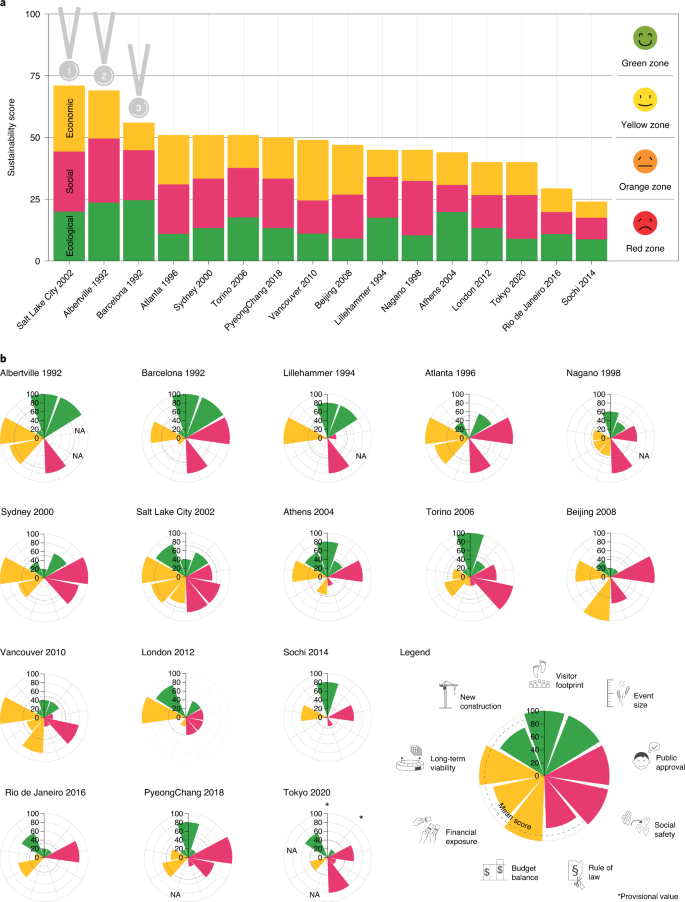

Individual host cities

Sustainability varies considerably across the sixteen host cities of the Olympic Games in the sample. Figure 5a divides the total scores for the 16 events into four intervals. While seven out of the 16 Olympics in our sample fall into the yellow zone of the second interval (oftentimes barely so, with just 50 or 51 points), viii fall into the problematic orange zone of the 3rd interval and i falls into the red zone of the bottom interval. None manages to achieve a score in the meridian interval (75 to 100 points), what nosotros call the greenish zone.

a, Ranking according to total scores. b, Individual scores. Salt Lake City 2002, Albertville 1992 and Barcelona 1992 were the most sustainable Olympic Games since 1992. Withal all iii still score in the yellow zone. None of the Olympic Games since 1992 has scored in the dark-green zone. Vancouver 2010 and London 2012 praised their own sustainability achievements merely do non score at the tiptop. The legend at the lesser right shows the maximum scores accomplished on each indicator. NA, not available.

The near sustainable Olympics, all in the yellow zone, were held in Common salt Lake Metropolis, United states, in 2002 (M = 71) and in Albertville, France, in 1992 (M = 69). Both were Winter Olympics. The Summertime Olympics of Barcelona in 1992 are in third identify, although with a considerably lower score (1000 = 56). Together with Albertville, they take the highest mean score in the ecological dimension amidst all cities in the sample.

That the gold and silver medals in sustainability go to Salt Lake Metropolis and Albertville is unexpected. Neither of the ii cities is very prominent in the literature on sustainability in mega-events nor had they made far-reaching claims about sustainability. The Salt Lake Urban center Olympics were overshadowed by a bribery scandal and the events of 11 September in the preceding year. The city aimed to use the Olympics primarily to improve its image and attract more tourists42, merely was not noted for its commitments to sustainability. In fact, it demonstrated a particular lack of attention to the social impacts of the effect, according to some35. The Albertville 1992 Olympics, while taking environmental considerations into account, were severely criticized for the environmental damage caused by the construction of new sports venues43.

Our results urge a re-consideration of the experiences of Salt Lake Metropolis and Albertville for future Olympic Games. Common salt Lake City scores highly because it has higher up-average scores across the board, although these are nowhere outstanding. Its economic functioning is particularly remarkable and the best in the sample, with express financial exposure, very good after-use of venues and a moderate price overrun of 24%. Albertville, by dissimilarity, stands out for its performance in the ecological dimension. While it congenital many new venues, it was a small-scale upshot with a moderate number of visitors and personnel, compared with other events in the sample, thus creating a insufficiently express ecological and material footprint.

At the tail end, the Winter Olympics in Sochi in 2014 and the Summer Olympics in Rio de Janeiro in 2016 feature the lowest sustainability scores. Equally our data show, the Olympics in Rio de Janeiro displaced a large number of residents for Olympics-related development and provided the occasion for the enactment of comprehensive legal exceptions. The resulting sports venues remained poorly used after the event, and cost overruns were the highest in the sample. Sochi is the only Olympics to fall into the bottom interval, or red zone. Side by side to extensive new construction and the high number of accredited participants, this is by and large due to its poor economic functioning: Sochi suffered the second-highest cost overruns in the sample, while not finding meaningful subsequently-use for nigh venues.

Outlook for Tokyo 2020 Olympics

The majority of data for our model are already available for Tokyo 2020 (Fig. five), to exist held in 2021, although some need to exist seen as provisional (marked with * in Fig. 5) due to the uncertainty effectually this result as a consequence of COVID-nineteen. Tokyo has substantial public financial exposure, with more than l% of the sports-related cost footed by the state. While the Olympics have not much interfered with the rule of constabulary, they have displaced more than 500 people. Past dissimilarity, new-venue construction is beneath average, with virtually 20% of venues being new venues. Figures for the number of visitors and accreditations are provisional at this time and based on organizers' forecasts. Overall, these Olympic Games score in the orange zone, at xl points, below the long-fourth dimension average of 48 points.

Discussion

The stakeholders of the Olympic Games pigment them equally paragons of sustainability. Our assay reveals that this is not the instance. The Olympic Games between 1992 and 2020 take a medium sustainability level. Salt Lake City 2002 and Albertville 1992 have the all-time records only did not accomplish high sustainability overall. There are no Olympics that score highly in all or even the bulk of the indicators of our model. Cities such equally Vancouver and London, which have marketed themselves every bit models of sustainable Olympic Games and take brash other Olympic hosts on sustainability, score below averagexi,44,45. This result suggests that sustainability rhetoric does not lucifer bodily sustainability outcomes.

Sustainability in the Olympics has besides significantly declined over time. Some recent Olympic Games have very poor sustainability, such every bit the Winter Games of 2014 in Sochi and the Summer Games of 2016 in Rio de Janeiro. This is despite the much-advertised priority of organizing sustainable Games since at least the 2010s. The power of the Olympic spectacle is not currently harnessed to transform unsustainable modes of global economic product, but to entrench them. This falls short of the humanist ideals of the Olympics to be a force for progress and improvement—for humanity and for the planet.

Nonetheless, our analysis shows that organizing more sustainable Olympic Games is possible. There are Olympic Games in our sample that have scored highly on private, if not on all, indicators. This event questions sceptics' claim that mega-events tin can never be sustainable. Nevertheless incisive reforms are required to upwardly the game in Olympic sustainability before these events can inspire and influence sustainable futures. These reforms demand to aim both at reducing resource input and at improving the governance of the Olympic Games to produce sustainable outcomes.

The following three deportment are feasible in the short run and would outcome in major improvements in sustainability. First, greatly downsize the outcome. This will pb to a gain on virtually all sustainability indicators by reducing resource requirements. It volition diminish the carbon emissions by visitors and bring down the ecological and fabric footprint by reducing the size and cost of the new infrastructure required. This measure also makes price overruns and deportation of people less likely. Reducing in-person presence of spectators can be compensated past providing immersive sports content in digital form. Second, rotate the Olympics among the same cities. This way, all required infrastructure volition already be in place, and the Olympic Games could be hosted with minimal social and ecological disruption and at minimal cost. 3rd and last, improve sustainability governance. This ways creating or mandating an independent body to develop, monitor and enforce credible sustainability standards. This action will improve the current situation, where each Olympic host city sets its own sustainability goals and remains unaccountable when not achieving them15.

There is currently strong resistance among Olympic stakeholders to such reforms as these could jeopardize revenue flows (in the case of downsizing), reduce the universal appeal of the Olympics (in the example of rotation) and impose stringent, non-negotiable commitments to sustainability (in the case of improved sustainability governance). Until such actions are taken, yet, cities and countries should rather spend public money on other measures to achieve sustainability, not on the Olympic Games.

Methods

Conceptual model

Our assay provides an evaluation of sustainability, which is a judgement on the degree of (un)sustainability, based on ex post data on the outcomes of the Olympic Games. We took our definition of sustainable mega-events (see the preceding) as the starting point for developing the conceptual model in Fig. 1 to evaluate the sustainability of the Olympic Games. The model started from current debates on global sustainability that posit the need to respect planetary biophysical boundaries while guaranteeing a minimum threshold of social well-being46,47. It therefore measures resource consumption, such every bit ecological and cloth footprints48,49; social protection and well-existence, such every bit social equity and social peace; and economic efficiency, such as toll overruns and long-term utilise of issue facilities.

The model features three indicators for each of the three dimensions of sustainability (ecological, social and economic). The utilize of three indicators per dimension increases reliability, reducing the effect of uncertainty and measurement errors. All indicators reverberate ex post data, except for Tokyo 2020, where we used the virtually recent estimates available by October 2020. Using ex post information corrects for the overwhelming say-so and political preference for ex ante predictions that may help to justify holding the Olympic Games vis-à-vis stakeholders only whose predictions are oft wrong28. The model contains both qualitative (text-based) indicators (rule of police, long-term viability) and quantitative indicators (all others), to allow a comprehensive assessment50.

The total of ix indicators were required to fulfil two basic criteria: they needed to be valid for evaluating the sustainability of the Olympic Games and data needed to exist bachelor28. We undertook two steps to ensure the validity of the model. In a first step, nosotros ascertained content validity by determining whether each of the nine indicators represented a major aspect both of the concept of sustainability as such and of the impacts of mega-events on sustainability. We did this through reviewing the existing literature24,33,51, and results are shown in Supplementary Table 1 in the columns 'justification' and 'relation to the literature'. Nosotros go beyond existing approaches to consequence sustainability by focusing non merely on the presence of sustainability policies and programmes but on outcomes52 and by focusing not and then much on the direction practices of the consequence itself27,53 equally on the wider impacts in the city and region.

In a second pace, nosotros ascertained attribution validity, determining whether the outcomes in the values of each indicator could plausibly exist attributed to the Olympic Games. This trouble of attribution is an of import one when attempting to evaluate any policy or intervention, non just the Olympic Games24,54. In choosing our indicators, we opted for a plausibility arroyo54, pregnant that we aimed to minimize the influence of confounding factors on the measured indicators to isolate, to the greatest degree possible, the affect of the Olympic Games (come across cavalcade 'plausibility of attribution' in Supplementary Tabular array 1). For this reason, we did not include indicators such as change in GDP, tourist arrivals, external image perception, air quality or others, as a plausible attribution of a modify in these to the Olympic Games is difficult to establish.

It is important to notation that at that place tin never be absolute certainty that the observed change in the indicators is due to the Olympic Games. This limitation is shared among all evaluations of social phenomena against an external intervention, from public wellness interventions to policy evaluations, and should not foreclose us from conducting such evaluations every bit long every bit nosotros tin demonstrate, as we do here, reasonable plausibility in the attribution of outcomes.

A comparative longitudinal assessment depends on the information availability of the least-well-documented event, which constrains the choice of indicators. While some Olympic Games are extensively documented (such as those of Vancouver and London, notably through the Olympic Games Bear on Studies24,55), others, in item older ones, are less so. As is the case with all evaluation designs, notably with those of complex phenomena such as the Olympic Games, nosotros needed to strike a compromise between comprehensiveness and feasibility54. We should therefore stress that while nosotros present the almost comprehensive longitudinal evaluation of the sustainability of the Olympic Games to date, this is but one possible evaluation and other conceptual models are possible.

Sample delimitation

Our sample contains all Olympic Games from 1992 to 2020 (N = 16). Nosotros accept called 1992 as a cut-off point for five reasons. First, this is when issues of environment and sustainability started to gain traction, both globally (Earth Summit 1992) and in the Olympic Games56. 2nd, this is the beginning of the menstruation when the Olympic Games began to grow considerably, with the explosion of revenues from sponsorship and broadcasting36, and therefore started to have larger impacts on their hosts. Third, from the Barcelona 1992 Olympics onwards, host cities likewise explicitly started to harness the Olympic Games for urban development, trying to leverage it for urban alter57. 4th, 1992 marks the indicate when the mega-event became a global phenomenon sensu stricto, with the integration of the onetime Eastern bloc into global capitalism. Fifth and concluding, 1992 is also a breaking point in data availability. Olympic Games before that twelvemonth are less well documented, and information technology proved difficult to populate data points for our model.

Data collection

Information collection presented a major endeavor, as mega-events are known for being opaque3,50. The absenteeism of coherent information to evaluate any aspect of the Olympic Games, not just their sustainability, is problematic, all the more so considering the exorbitant public expenditure. Role of this opaqueness results from the absence of systematic data collection across events, except for a small-scale number of indicators past the IOC. The IOC's Olympic Games Touch (OGI) initiative—a series of contained reports before and later the Olympic Games based on indicator sets—sought to modify that, with a view to comprehensively measuring the outcomes of the Olympic Games and creating a standard for sustainability beyond Olympic host citiesfifty. Launched in 2000, OGI featured a series of 126 indicators in the three spheres of economic, environmental and sociocultural impacts that are monitored over a period of 12 years. The IOC required that host cities mandate an independent research partner to carry out the study according to a gear up of predefined instructions24. The total wheel of 4 reports, however, was merely completed for a unmarried Olympic Games, Vancouver 2010. Host cities complained that the OGI was too cumbersome, so the IOC reduced the number of reports and somewhen abandoned OGI altogether in January 2017, replacing information technology with a series of sustainability reports issued by the Olympic organizing committees28,58. This has removed the merely independent, systematic data source for assessing sustainability in the Olympic Games and put in its place anecdotal reports that are issued past the very organization that is under review, thus creating a conflict of interest.

Another element of the opaqueness results from carelessness, obfuscation and sometimes deliberate destruction of records. Thus, in the run-up to the Sochi Olympic Games, accounts were sometimes non kept when under time pressure level. Said 1 investor: "nosotros were in such a hurry in the end that nosotros didn't count the money"59. In many cases, crucial information is not collected, non reported, not reported transparently or not accessible to the public or to researchers. For the Nagano 1998 Olympics, hosts even deliberately destroyed function of the fiscal recordssixty.

Due to this opaqueness, we were able to source simply three of the nine indicators from single data sources: data for 'company footprint' and 'event size' could exist collected from official reports of the Olympic Games, while data for 'upkeep balance' were sourced from a separate study3. For the remaining half-dozen indicators, nosotros used a mixture of the following sources: bid books and official reports from the Olympic Games, independent third-party assessments (such as national audit chambers), academic literature, media reports and reports by non-governmental organizations. Many of these sources were available online for more contempo events and available in athenaeum for older events. Standardized definitions for each indicator ensured commensurability of data from different sources. For each information bespeak, we besides assessed the reliability of the source, including only data points with at least medium-loftier reliability in the analysis.

While we collected data amidst the author team for eight editions of the result, nosotros contracted experts to collect data and sources for another eight editions (Barcelona, Lillehammer, Atlanta, Nagano, Salt Lake City, Athens, Beijing and Vancouver). This was necessary because we either lacked the skills to read documents in the local language or needed to access archives in situ. All contractors were academics, and most of them had washed previous work on the specific mega-event we commissioned them to piece of work on. They were given a strict set up of instructions and definitions to follow and were required to provide a scan of the original source for each data point. The projection squad validated all information points and cross-checked them against each source to ensure reliability.

Data scoring

We scored each indicator on a scale from 0 to 100 in increments of twenty, where 0 ways least sustainable and 100 means most sustainable. Rules for assigning scores are detailed in Supplementary Table 1. We chose stop points of scores either according to natural limits (for example, in the indicator 'new construction' a score of 100 was assigned where there was no new construction) or, where these were not evident, by choosing the most extreme case in the sample. Increments betwixt the extreme points were then defined in such a style as to create intervals of roughly equal size. To accommodate for size differences betwixt the Summer and the Winter Olympic Games, we practical different scales for these two sub-groups for ii indicators ('company footprint' and 'event size') co-ordinate to the aforementioned scoring rules (Supplementary Table 1).

The presence of values at both extremes of the scoring scale (Fig. 2b) indicates that our scoring rules are off-white in the sense of not beingness also strict (thus making it unlikely to obtain scores of 100) or too lenient (making information technology like shooting fish in a barrel to obtain loftier values).

Whereas scoring of numeric indicators was straightforward, for the 2 qualitative indicators, three scorers assigned scores independently from each other to increase reliability. They then discussed and resolved any differences in their scores. Out of 144 data points, 7 (iv.nine%) are missing. There is no reason to assume a systematic pattern in missing values that would bias results. Missing values were therefore ignored for calculating mean scores and mean differences between groups.

For evaluating the overall sustainability of an Olympic Games, we used a score-card approach24, where we calculated the mean across all nine indicators, assigning equal weight to each score. This is a measure out of relative sustainability: a score of 100 does non hateful, therefore, that an event is sustainable in the sense of respecting planetary boundaries while guaranteeing social well-being46. The choice of adding scores instead of multiplying them assumes that a compensation is possible between the unlike dimensions of sustainability, that is, that a deficiency in one score tin be compensated by a surplus in another55.

Data analysis

The sample of 16 editions makes this a set of indicators on the Olympic Games that can be analysed with inferential statistics. The sample size allows performing statistical tests with sufficient statistical power (π > 0.eight) for large issue sizes (>0.8) at a probability level of 0.0561. It does non, however, provide sufficient statistical ability to find medium or small effect sizes.

We checked bivariate correlations among the nine indicators (reported in Supplementary Table 2) to rule out strong correlations (r > 0.eight), which could question the unique conceptual contribution of specific indicators. No strong correlations were found, and merely iii of the 36 correlations are pregnant.

We used descriptive statistics (frequencies, hateful values and standard deviations) to narrate the dataset and inferential statistics (ii-tailed independent samples t test of mean value differences) to identify significant differences between groups. Mean scores were rounded to the next nearest integer for presentation in the manuscript. We used correlation models with Pearson's r as a standardized correlation coefficient for estimating the linear trends of sustainability in Fig. 3 at a significance level of 0.05 (two-tailed).

We too constructed an exploratory regression model to examine whether we could predict sustainability scores with host context indicators24, such as the level of income in a country, the degree of abuse or the size of the host city. We did not find any pregnant effects (which might simply exist due to a lack of statistical power, see the preceding) and therefore do not report results here.

Limitations

There is no accustomed definition of the sustainability of large events. Despite justification of our choice of indicators, our model is just one model of sustainability. It is a systematic and evidence-based model, but, similar all models of sustainability, it withal reflects a subjective sentence virtually what to include in defining sustainability. Other models are possible and might result in dissimilar outcomes. The aforementioned caveat applies to the scoring, where other cut-offs and intervals are possible (which would, all the same, not affect the relative ranking of hosts, as the underlying data remain the same).

We besides did non include potential catalyst effects of the Olympic Games on sustainability due to the absence of reliable and comparable data and to difficulties of plausible attribution. Effects typically claimed include long-term paradigm and growth benefits, inspiring people to accept upwardly sport, lead a healthier lifestyle or go more conscious of the environment, or creating peace and intercultural understanding. In full general, yet, evidence is thin for claims that seek to aspect to sports the role of a larger force for bringing near social, economic and ecological benefits62,63,64.

Information availability

The dataset and statistical analysis are available in the mega-event dataverse on Harvard dataverse at https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/ZARR6A.

References

-

Olympic Marketing Fact File (IOC, 2019).

-

Wade, S. & Yamaguchi, M. Tokyo Olympics say costs $12.6B; audit report says much more. AP NEWS (20 December 2019); https://apnews.com/eb6d9e318b4b95f7e53cd1b617dce123

-

Flyvbjerg, B., Budzier, A. & Lunn, D. Regression to the tail: why the Olympics blow up. Environ. Programme. A https://doi.org/10.1177/0308518X20958724 (2020).

-

Müller, M. The mega-event syndrome: why then much goes wrong in mega-event planning and what to do about information technology. J. Am. Plann. Assoc. 81, half dozen–17 (2015).

-

Sachs, J. D. et al. Half-dozen transformations to accomplish the Sustainable Development Goals. Nat. Sustain. two, 805–814 (2019).

-

Roy, A. & Deshmukh, R. Events Industry Market: Opportunities and Forecast, 2019–2026 (Allied Market Research, 2020).

-

Poynter, M., Viehoff, V. & Li, Y. (eds) The London Olympics and Urban Development: The Mega-Effect City (Routledge, 2015).

-

Viehoff, V. & Poynter, G. Mega-Result Cities: Urban Legacies of Global Sports Events (Routledge, 2016).

-

Kraas, F. et al. Humanity on the Motility: Unlocking the Transformative Ability of Cities (German Informational Council on Global Change, 2016).

-

van Vliet, J. Directly and indirect loss of natural expanse from urban expansion. Nat. Sustain. two, 755–763 (2019).

-

Hayes, Thou. & Horne, J. Sustainable development, shock and awe? London 2012 and civil social club. Sociology 45, 749–764 (2011).

-

Gaffney, C. Between discourse and reality: the un-sustainability of mega-outcome planning. Sustainability 5, 3926–3940 (2013).

-

Boykoff, J. & Mascarenhas, G. The olympics, sustainability, and greenwashing: the Rio 2016 summer games. Majuscule. Nat. Social. 27, ane–eleven (2016).

-

Hall, C. Yard. Sustainable mega-events: beyond the myth of balanced approaches to mega-event sustainability. Event Manag. sixteen, 119–131 (2012).

-

Geeraert, A. & Gauthier, R. Out-of-control Olympics: why the IOC is unable to ensure an environmentally sustainable Olympic Games. J. Environ. Policy Plan. 20, 16–30 (2018).

-

Liang, Y.-W., Wang, C.-H., Tsaur, South.-H., Yen, C.-H. & Tu, J.-H. Mega-event and urban sustainable development. Int. J. Event Festiv. Manag. 7, 152–171 (2016).

-

Meza Talavera, A., Al-Ghamdi, S. G. & Koç, 1000. Sustainability in mega-events: across Qatar 2022. Sustainability 11, 6407 (2019).

-

Mol, A. P. J. & Zhang, 50. in Olympic Games, Mega-Events and Civil Societies: Globalization, Environment, Resistance (eds Hayes, G. & Karamichas, J.) 126–150 (Palgrave, 2012); https://doi.org/10.1057/9780230359185_7

-

O'Brien, D. & Chalip, L. in Tourism Management: Analysis, Behaviour and Strategy (eds Woodside, A. K. & Martin, D.) 318–338 (CABI, 2008).

-

Olympic Calendar 2020+5 (IOC, 2021).

-

IOC Sustainability Strategy (IOC, 2017).

-

Sport equally an Enabler of Sustainable Development (United Nations General Assembly, 2018).

-

UN and Tokyo 2020, leverage power of Olympic Games in global sustainable development race. United nations News (14 November 2018); https://news.un.org/en/story/2018/11/1025711

-

Vanwynsberghe, R. The Olympic Games Impact (OGI) study for the 2010 Winter Olympic Games: strategies for evaluating sport mega-events' contribution to sustainability. Int. J. Sport Policy Polit. 7, ane–18 (2015).

-

Müller, Yard. et al. Dataset: Sustainability of the Olympic Games (Harvard Dataverse, 2021); https://doi.org/x.7910/DVN/ZARR6A

-

Houlihan, B., Bloyce, D. & Smith, A. Developing the research agenda in sport policy. Int. J. Sport Policy Polit. 1, ane–12 (2009).

-

Zifkos, G. Sustainability everywhere: problematising the 'sustainable festival' phenomenon. Tour. Plan. Dev. 12, 6–19 (2015).

-

Chappelet, J.-L. Beyond legacy: assessing Olympic Games operation. J. Glob. Sport Manag. 4, 236–256 (2019).

-

O'Neill, D. W., Fanning, A. L., Lamb, Westward. F. & Steinberger, J. K. A skilful life for all within planetary boundaries. Nat. Sustain. ane, 88–95 (2018).

-

Neumayer, E. Weak Versus Potent Sustainability: Exploring the Limits of Two Opposing Paradigms (Edward Elgar, 2003).

-

2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development (United Nations General Assembly, 2015)

-

Adoption of the Paris Understanding FCCC/CP/2015/L.9/Rev.1 (UNFCCC, 2015).

-

Getz, D. Developing a framework for sustainable event cities. Result Manag. 21, 575–591 (2017).

-

Smith, A. Theorising the relationship between major sport events and social sustainability. J. Sport Bout. 14, 109–120 (2009).

-

Minnaert, L. An Olympic legacy for all? The non-infrastructural outcomes of the Olympic Games for socially excluded groups (Atlanta 1996–Beijing 2008). Tour. Manag. 33, 361–370 (2012).

-

Horne, J. & Whannel, G. Agreement the Olympics (Routledge, 2016).

-

Smith, A. Events and Urban Regeneration: The Strategic Apply of Events to Revitalise Cities (Routledge, 2012).

-

Panagiotopoulou, R. The legacies of the Athens 2004 Olympic Games: a bitter–sweet burden. Contemp. Soc. Sci. 9, 173–195 (2014).

-

Searle, Thousand. Uncertain legacy: Sydney'due south Olympic stadiums. Eur. Plan. Stud. 10, 845–860 (2002).

-

Gold, J. R. & Gold, 1000. Grand. 'Bring it under the legacy umbrella': Olympic host cities and the irresolute fortunes of the sustainability calendar. Sustainability five, 3526–3542 (2013).

-

Holden, Thou., MacKenzie, J. & VanWynsberghe, R. Vancouver'south promise of the globe'southward showtime sustainable Olympic Games. Environ. Programme. C 26, 882–905 (2008).

-

Andranovich, K., Burbank, M. J. & Heying, C. H. Olympic cities: lessons learned from mega-event politics. J. Urban Aff. 23, 113–131 (2001).

-

Chappelet, J.-L. Olympic environmental concerns equally a legacy of the Winter Games. Int. J. Hist. Sport 25, 1884–1902 (2008).

-

Moore, Southward., Raco, 1000. & Clifford, B. The 2012 Olympic learning legacy agenda—the intentionalities of mobility for a new London model. Urban Geogr. 39, 214–235 (2018).

-

Temenos, C. & McCann, E. The local politics of policy mobility: learning, persuasion, and the production of a municipal sustainability fix. Environ. Programme. A 44, 1389–1406 (2012).

-

Steffen, Due west. et al. Planetary boundaries: guiding human development on a irresolute planet. Science 347, 1259855 (2015).

-

Raworth, Grand. Doughnut Economics: Seven Ways to Think Like a 21st-Century Economist (Random House, 2018).

-

Borucke, M. et al. Accounting for demand and supply of the biosphere's regenerative capacity: the National Footprint Accounts' underlying methodology and framework. Ecol. Indic. 24, 518–533 (2013).

-

Wiedmann, T. O. et al. The fabric footprint of nations. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. United states 112, 6271–6276 (2015).

-

Leonardsen, D. Planning of mega events: experiences and lessons. Plan. Theory Pract. viii, 11–30 (2007).

-

Scrucca, F., Severi, C., Galvan, N. & Brunori, A. A new method to assess the sustainability performance of events: application to the 2014 Globe Orienteering Championship. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 56, 1–11 (2016).

-

Laing, J. & Frost, Due west. How greenish was my festival: exploring challenges and opportunities associated with staging green events. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 29, 261–267 (2010).

-

Holmes, K., Hughes, M., Mair, J. & Carlsen, J. Events and Sustainability (Routledge, 2015).

-

Habicht, J. P., Victora, C. Yard. & Vaughan, J. P. Evaluation designs for adequacy, plausibility and probability of public wellness programme functioning and impact. Int. J. Epidemiol. 28, ten–xviii (1999).

-

Olympic Games Affect Study—London 2012 Postal service-Games Written report (Univ. East London, 2015).

-

Cantelon, H. & Letters, One thousand. The making of the IOC environmental policy as the tertiary dimension of the Olympic motility. Int. Rev. Sociol. Sport 35, 294–308 (2000).

-

Monclús, F.-J. The Barcelona model: and an original formula? From 'reconstruction' to strategic urban projects (1979–2004). Plan. Perspect. 18, 399–421 (2003).

-

Olympic Games Impact Study (Middle for Olympic Studies, 2020).

-

Fedorova, M. Postolimpiyskiy sindrom. Kommersant (17 Dec 2014).

-

Baade, R. A. & Matheson, V. A. Going for the gilt: the economics of the Olympics. J. Econ. Perspect. 30, 201–218 (2016).

-

Tabachnick, B. G. & Fidell, L. Using Multivariate Statistics (Pearson, 2012).

-

Coalter, F. A Wider Social Role for Sport: Who'south Keeping the Score? (Routledge, 2007).

-

Billings, S. B. & Holladay, J. Due south. Should cities go for the gilt? The long-term impacts of hosting the Olympics. Econ. Inq. 50, 754–772 (2012).

-

Reis, A. C., Frawley, S., Hodgetts, D., Thomson, A. & Hughes, K. Sport participation legacy and the Olympic Games: the case of Sydney 2000, London 2012, and Rio 2016. Effect Manag. 21, 139–158 (2017).

Acknowledgements

We thank all who collaborated with us on the data collection. We are grateful to F. Bavaud, J. Grieshaber, J.-Due west. Lee, C. Guala and K. Peter for contributing to this paper in their own ways. The Swiss National Science Foundation (SNSF) funded the research of this paper under the grant Mega-events: growth and impacts, grant number PP00P1_172891.

Author information

Affiliations

Contributions

M.M. designed the research, analysed the data and wrote the manuscript. M.M., S.D.W., C.G., Grand.H. and A.L. developed the database. Chiliad.Thousand., S.D.W., D.G., Thousand.H. and A.Fifty. collected and assembled the information.

Respective writer

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Peer review information Nature Sustainability cheers Meg Holden, John Short and the other, anonymous, reviewer(southward) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Publisher'south annotation Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this commodity

Müller, M., Wolfe, S.D., Gaffney, C. et al. An evaluation of the sustainability of the Olympic Games. Nat Sustain 4, 340–348 (2021). https://doi.org/ten.1038/s41893-021-00696-v

-

Received:

-

Accepted:

-

Published:

-

Issue Date:

-

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1038/s41893-021-00696-5

Farther reading

madridyalmled1962.blogspot.com

Source: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41893-021-00696-5

Postar um comentário for "Choice Current Reviews for Academic Libraries Peer Review"